Appearance

人工智能(AI)

2026-02-01 Why software stocks are getting pummelled

On January 29th SAP, whose applications are widely used to manage everything from inventory to payroll, said during an earnings call that it expected a “slight deceleration” in its cloud-based software business in 2026. Its share price plummeted by 15%.

That of ServiceNow, whose tools help businesses automate various tasks, dropped by 13%, even though in the latest quarter its revenue grew faster than analysts had expected.

Even software companies that released no news suffered, with Salesforce down by 7% and Workday by 8% (see chart 1).

The carnage reflects growing nervousness over the future of the software industry in the age of artificial intelligence. The value of listed American enterprise-software companies is down by 10% over the past year.

But could an AI upheaval be just around the corner? Pundits have focused on two threats. The first is from AI coding tools. Anthropic’s Claude Code and OpenAI’s Codex, among others, help programmers to write code far more quickly. “Vibe coding” startups, such as Lovable and Base44, allow even laymen to make software by giving chatbots simple instructions. The fear is that these tools are allowing companies to create much of the software they need themselves. The other threat is that AI-native enterprise-software startups—such as Attio, which sells customer-management tools, or Glean, which offers a product that allows companies to perform advanced searches on their internal data—will steal business from the incumbents.

For most companies, building software is a distraction from their core business. The trend for decades has been in the opposite direction.

AI will continue to improve. But it is also likely to get more expensive. At present Silicon Valley heavily subsidises its price. That cannot last for ever. OpenAI expects to burn $17bn in cash this year. Microsoft’s share price took a beating last week as investors winced at its enormous spending on the data centres underpinning the technology. Eventually these companies will need to demonstrate a return on all that investment, which is bound to mean higher prices.

When that happens, dedicated software companies will have an advantage. That is partly for the simple reason that they can spread the cost of developing a program over their many customers. But it is also because they are better at using AI to write code. A recent paper by Fiona Chen and James Stratton of Harvard University examined the productivity of programmers using AI, and found that it resulted in an increase in output (measured by the number of tasks completed) only for those at companies selling software.

What of the software industry’s AI-native rivals? Here, too, the fear of disruption may be overblown. Incumbent software providers have been investing heavily to embed AI features in their products. To speed the effort, they have been on a dealmaking spree. Acquisitions last year included Workday’s purchase of Sana Labs, a Swedish AI startup, and ServiceNow’s purchase of MoveWorks, another AI company. The software giants have deep pockets to fund more investments: together Salesforce, SAP, ServiceNow and Workday generated almost $30bn in free cashflow last year. Their products are also sticky, because it is expensive and risky for large companies to switch software, and the companies can use their scale to quickly gather feedback on new AI features.

Even if the price of accessing AI goes up, the technology should still bring down the cost of developing software over time. That could lead to more, not less, spending on software, as companies use it to replace tasks still done by humans.

A paper published by the Bank of France finds that such spending is reasonably elastic. In our analysis of official data on American business-software investment, we similarly find that a 10% decline in software prices is associated with a 20% rise in spending. Software may eventually eat the world, but so far it has only nibbled around the edges at most companies. It could soon take a much bigger bite.

2026-01-15 Innovations in energy and finance are further inflating the AI bubble

Power suppliers are overwhelmed by demand for electricity to run AI chips in vast data centres. Ercot, Texas’s grid operator, has received requests for more than 226 gigawatts (GW) of power by 2030, nearly 100 times more than it approved in 2022. President Donald Trump has joined a chorus of Americans worried that the insatiable power demand from AI projects will drive up electricity prices. On January 13th he promised citizens they would not “pick up the tab”. Tech giants such as Microsoft would instead.

For a few years before xAI, his model-maker, joined the AI race, tech giants hooked their data centres directly to America’s electricity grid. But the more demand there was, the longer it took to secure a connection—and Mr Musk was in a hurry to catch up with rivals such as OpenAI. So he pioneered what SemiAnalysis, a research firm, christened the “BYO” (bring-your-own) alternative to grid-based energy. When xAI built a big cluster of graphics processing units (GPUs) in a record four months in Tennessee in 2024, it literally trucked in gas turbines and engines. Initially, this was a stopgap measure. But with grid connections now taking as long as five years to secure, BYOs are here to stay.

Last monthBoom, which is building ultra-fast planes, announced that it would supply 29 natural-gas turbines based on the same technology as its jet engines to Crusoe, a data-centre developer. Wärtsilä(WRTBY), a Finnish firm that makes engines for cruise ships, also sells them for data centres. Other promising new technologies such as fuel cells may be harnessed, too. All told, Goldman Sachs reckons that up to a third (or 25GW) of incremental data-centre capacity will be built off-grid in America over the next five years. That will mean data centres can spring up more quickly.

Adjacent to a $20bn fundraising that xAI completed in early January, it will lease $5.4bn-worth of Nvidia GPUs from a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) set up by Valor Equity Partners, its long-standing backer. Both Meta and Oracle have also used SPVs to reduce the strain that data-centre projects are placing on their balance-sheets. Meta whipped up an extraordinary concoction of private capital, corporate bonds and debt guarantees to raise $30bn for a mammoth data centre in Louisiana called Hyperion. Fittingly, the SPV for the project is named after a sugar-coated New Orleans pastry called a beignet. Oracle has also reportedly raised $66bn in off-balance-sheet financing through SPVs, all to support OpenAI, which has so far proved to be far better at making deals than making money.

The size of such deals—as well as their concentration among a small group of borrowers—is giving the heavily regulated banking industry indigestion. It is happy to arrange bond issues for highly profitable hyperscalers. But the less creditworthy the counterparty, the trickier it is to hold loans on a bank’s books for long. This is providing opportunities for private-credit firms, often funded by life insurers, who are either originating loans to data-centre borrowers or buying bespoke tranches of the banks’ AI-loan portfolios. The market is potentially huge. Morgan Stanley reckons that data-centre financing involving private-credit firms will reach $800bn in the five years to 2030—or about half the total amount it expects to be borrowed in the data-centre boom. Yet many of the financiers involved are making it up as they go along.

In the energy markets BYO power brings higher costs and exposes data centres to greater risk of equipment failure than they would otherwise have on the grid.

As for the credit markets, they are a good place to raise money now that AI investment can no longer be entirely self-funded. But the spillovers may also be dangerous. Only a few firms are making reliable profits from AI. If that does not change, there is a risk of a credit meltdown that could rock the financial system and the economy more broadly. Then the world will need a new type of ingenuity—at picking up the pieces.

2026-01-12 Which countries are adopting AI the fastest?

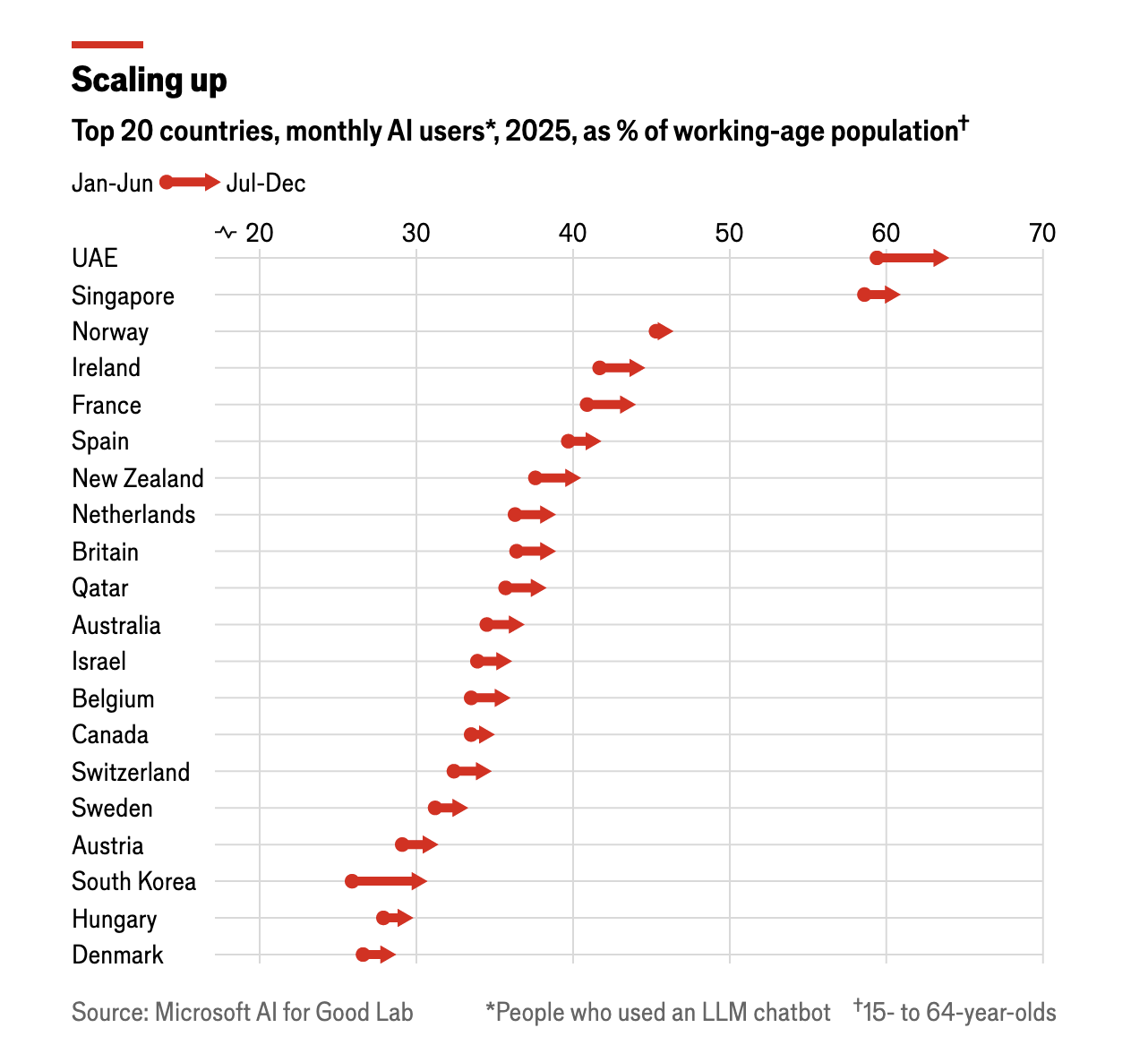

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) entered the mass market just three years ago, but by the end of 2025 some 16% of the world’s working-age population used generative-AI tools each month.

America and China lead the world in developing the technology, but they are not the ones adopting it fastest.

Residents of the United Arab Emirates, Singapore, Norway, Ireland and France were the top AI adopters. In both the UAE and Singapore more than 60% of the working-age population used AI chatbots.

South Korea is the fastest-growing market; there the number of working-age users increased by 18.5% from the first to the second half of last year. Viral AI-generated images—photos transformed into Japanese anime-style figures—caught Koreans’ attention, and models’ grasp of their language is fast improving.

People in rich countries tend to use AI chatbots more than those in poor ones do , but GDP per person is an imperfect guide to how quickly a country takes up the technology. America ranks only slightly above the Czech Republic and below Poland, despite being far richer than both. India appears to be adopting AI much faster than incomes there would suggest, while China is slightly below trend. Relative to GDP, people in Jordan and Vietnam are particularly keen users of LLMs.

DeepSeek is especially popular in Africa, where usage per person is between two and four times that of other regions. It also leads in places where American technology is restricted: the countries where DeepSeek has the largest estimated market share are China (89%), Belarus (56%), Cuba (49%), Russia (43%) and Iran (25%).

2026-01-08 AI is transforming the pharma industry for the better

Ai-designed molecules show an 80-90% success rate in early-stage safety trials, compared with a historical average of just 40-65%. It will be years before it becomes clear whether success rates rise in later-stage trials, too. But even if they do not, one model suggests that early-stage improvements alone could increase the success rate across the entire pipeline from 5-10% to 9-18%.

The industry is also wringing efficiencies out of its business using AI, in areas from clinical documentation to HR. McKinsey reckons that if AI is fully utilised by the pharma industry—no doubt with its consultants’ assistance—it could provide a boost worth $60bn-110bn annually.

The technology is already changing how the pharma industry works. A new generation of AI-native biotech startups—particularly in America and China—is emerging. Pharma companies are increasingly forming alliances with AI-biotech firms, as well as with technology giants including Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Nvidia. And those big tech firms have their own ambitions in health. Isomorphic Labs, a spin-out from Google DeepMind, is trying to design entirely new therapeutic molecules from scratch inside a computer. Nvidia, too, has a generative-AI platform for drug discovery. Both firms are signing deals to offer design services to pharma companies. And in October Nvidia teamed up with Eli Lilly, the world’s most valuable drugmaker, to build the pharma industry’s most powerful supercomputer.

All this means that some of the value of drug discovery may be captured by tech giants. For now, pharma firms have many clear advantages, including heaps of data, scientists who know the field and long experience of shepherding new drugs through a maze of regulation. Over time, though, as parts of biology become more of a computational problem that can be solved with technology, such advantages could be eroded. Pharma firms may need to buy in ai expertise in the same way that they buy early-stage assets from biotech firms today.

As drug discovery becomes more efficient, governments will need to turn their attention to other potential bottlenecks in the system, such as regulation and trials. America’s Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency are themselves starting to use ai to screen the mountains of data they receive. As the number of drug candidates rises, faster regulatory reviews will be needed to avoid a logjam. Governments could also do more to encourage the sharing of patient data with AI companies in privacy-preserving ways so that AI models—and drug discovery—can improve.

Patents, too, will need rethinking. Today, long patent lives let pharma firms recoup the investments they make, encouraging them to undertake the risky business of drug discovery. Yet if the costs and riskiness of innovation fall dramatically, then patent terms (which typically provide 10-15 years of market exclusivity) may need to become shorter. ai brings good news for drug innovation. But to ensure that it benefits both the makers and takers of new drugs, the industry and its regulators will need to adjust to this new reality.

2026-01-07 The “ChatGPT moment” has arrived for manufacturing

According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), an industry association, there were around 4.7m industrial robots operational worldwide as of 2024—just 177 for every 10,000 manufacturing workers. Having risen through the 2010s, annual installations surged amid the pandemic-era automation frenzy, but flattened off afterwards, with 542,000 installed in 2024.

That has been mirrored in the wider market for factory-automation equipment, including sensors, actuators and controllers, which has faced tepid demand over the past few years amid a slowdown in manufacturing, particularly in Europe. Despite a stellar performance during the pandemic, shares in the industry’s big suppliers have lagged behind those of other rich-world companies since the beginning of 2024 (see chart 1).

Yet analysts see 2026 as an inflection point. The IFR reckons that annual robot installations will increase to 619,000 this year (see chart 2). Roland Berger, a consultancy, forecasts that inflation-adjusted growth in sales of industrial-automation equipment as a whole will rise from a meagre 1-2% in 2025 to 3-4% in 2026, then notch up 6-7% for the remainder of the decade.

“The ChatGPT moment for robotics is here,” declared Jensen Huang, boss of Nvidia, a chipmaker and darling of the AI boom, on January 5th.

Hints of the future can already be glimpsed at the Bavarian factories of Siemens, itself a maker of automation equipment, in Amberg and Erlangen. The Amberg factory, which makes 1,500 variants of machine controllers, today produces around 20 times what it did when it opened in 1989, but with approximately the same number of workers. Robotic arms, many of them made by Universal Robots, whose parent company is Teradyne, an American business, do much more than pick up eggs. In glass enclosures they move swiftly about, welding, cutting, assembling and inspecting. Workers monitor and control production from computers attached to the machines.

Factory hardware has come a long way in the past few decades. Robotic arms that once moved along three axes—up and down, left to right, front to back—typically now move along six. Sensors and cameras guide their motion. A single robot is often able to perform several manufacturing steps. They have also plunged in price as production has scaled up and Chinese suppliers have entered the business.

Even bigger advances are taking place in the software that makes machines and factories hum. Robots were once rigidly designed for one activity. That required manufacturers to be “stuck in a moment of time” in order to capture the benefits of automation, notes Ben Armstrong of the MIT Industrial Performance Centre. Now the machines can be reprogrammed for another job with a tweak to their code. For example, robots that were previously used by Foxconn, a Taiwanese manufacturer, to put the circular “home” button on earlier generations of iPhones were repurposed to install microchips. Such flexibility has further improved the lifetime return on investment in robots.

Software is changing manufacturing in other ways, too. Computerised simulations known as “digital twins” are making it quicker and cheaper to test product designs and manufacturing processes; two-dimensional, paper-based blueprints have been replaced by precise, three-dimensional reproductions. Suppliers of automation gear have piled in. Last year Siemens bought Altair, an industrial-software firm, for $10bn, its largest acquisition ever. Software, which typically generates a higher margin than hardware, now accounts for a third of sales in the conglomerate’s industrial-automation division.

- 2024-10-30 Siemens strengthens leadership in industrial software and AI with acquisition of Altair Engineering

- 2025-03-26 Siemens acquires Altair to create most complete AI-powered portfolio of industrial software

Generative AI promises to take this transformation a step further. Until recently, precisely modelling the actions of a robot was often impossible owing to the many variables involved, a problem known as the “sim-to-real gap”. Simulations tended to break the moment lighting or the shape of an object changed. Supersized AI models, trained on vast amounts of data from sensors and cameras, may help solve that. As simulations become more accurate and detailed, it may be possible to program robots to approach a physical task much as a human would, perceiving, understanding and then reacting to the situation.

The prospect of harnessing “physical AI” to revolutionise manufacturing has generated much excitement. During the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas this week, Nvidia unveiled a suite of chips and freely available AI models designed specifically for robots. In October SoftBank, a Japanese conglomerate with big AI ambitions, announced it would acquire the robotics division of ABB, a Swiss industrial giant. Startups from Silicon Valley to Shanghai are building humanoid robots that they hope will one day replace factory workers. So is Elon Musk.

The automation industry’s incumbents are also investing heavily in physical AI. Peter Koerte, Siemens’s chief technologist, reckons that AI will become the “brains” of factories much as machines have become their “muscles” (albeit with human oversight). In September his firm announced a deal with German machine-makers to pool anonymised data from their hardware and build AI models for industrial use. On January 6th it said that it would expand its partnership with Nvidia and develop, among other things, an AI-powered tool for building digital twins. Last year Hitachi, a Japanese industrial giant that is also working with Nvidia, unveiled a new AI-powered software platform that ingests and analyses data from the many sensors and cameras across a factory and can alter operations in response.

Some now talk of factories becoming not just automated, but autonomous. “Imagine a factory where machines anticipate needs before they arise, where material moves seamlessly without human intervention and production lines adjust in real time to changes in demand or disruptions,” gushed Tessa Myers of Rockwell Automation, an American machine-maker, in November. The company is piloting the idea at a small facility in Singapore.

The result of all this may be a very different type of factory. With each robot able to perform a wide array of tasks, shop floors may no longer need to be designed around lengthy assembly lines. Combine that with falling hardware costs and many firms may soon find it viable to spread their manufacturing across a network of smaller plants.

For years the trend has been towards ever larger sites, fashionably called **“gigafactories”, as manufacturers have sought economies of scale. But smaller factories would have plenty of advantages. They could be built closer to urban centres, making it easier to bring in the workers who, at least for the time being, will remain both essential and difficult to find. Proximity to customers would also be useful, particularly given the persistence of tariffs. And a more dispersed manufacturing footprint would reduce the risk that a failure at a single factory becomes a crisis. The factory of the future will look very different from what Smith imagined—and may be even more transformational.

2026-01-05 An AI revolution in drugmaking is under way

Dr Schwab works for GSK, a drug company. His job is to reimagine the future of drugmaking using that similarly trendy branch of computer science, artificial intelligence (AI). He is applying this to transferring as much of the load as possible from glassware to computers: in silico drug design, rather than in vitro.

To this end he is developing a software tool called Phenformer, which he is training to read genomes. By linking genomic information with phenotypes—the biological term for the bodily and behavioural outcomes of particular genetic combinations—Phenformer learns how genes drive disease. That allows it to generate novel hypotheses about particular illnesses and their underlying mechanisms.

Insilico Medicine, a biotech firm in Boston, seems to have been the first to apply the new generation of AI, based on so-called transformer models, to the business of finding drugs.

Insilico now has a pipeline of more than 40 AI-developed drugs it is assessing for conditions such as cancers and diseases of the bowels and kidneys. And its approach is spreading. One projection suggests annual investment in the field will rise from $3.8bn in 2025 to $15.2bn in 2030.

And last October Eli Lilly, another pharma giant, announced a collaboration with Nvidia, the firm whose chips are widely used to train and run transformer-based AI models, to build the industry’s most powerful supercomputer, and thus speed up drug discovery and development.

Given the pharmaceutical industry’s weird economics—candidate drugs entering clinical trials have a 90% failure rate, bringing the cost of developing a successful one to a whopping $2.8bn—even marginal improvements in efficiency would offer big gains. Reports from across the industry suggest that AI has begun to deliver these. AI-designed drugs are whizzing through the preclinical phase (that before human trials begin) in only 12-18 months, compared with three to five years previously. And the success of AI-designed drugs in safety trials is better too. A study published in 2024, of their performance in such trials, found an 80-90% success rate. This compares with historical averages of 40-65%. That, in turn, boosts the overall rate of getting drugs successfully through the entire pipeline to 9-18%, up from 5-10%.

Designing a new drug generally starts by screening small organic molecules for promising biological activity. AI can sift through libraries of tens of billions of these, testing properties such as potency, solubility and toxicity using software emulations, with no need for real molecules to get anywhere near test tubes. Jim Weatherall, one of those in charge of this activity at AstraZeneca 阿斯利康(AZN), yet another big drug company, says this sorts the wheat from the chaff twice as fast as before, and that over 90% of the firm’s small-molecule discovery pipeline is now assisted by AI.

AI is also helping improve trial design. One approach involves AI “agents” that behave as if they think and reason. Back at GSK, Kim Branson, head of AI, gave your correspondent a demonstration of an agent-based system called Cogito Forge. Prompted with a question about biology, Cogito Forge can write its own code to help answer that question, gather appropriate datasets, glue them together and then create a presentation—complete with charts showing the conclusions it has drawn.

From there it can generate a hypothesis about a disease, including testable predictions, and try to verify or falsify this with a literature search. That search employs three agents: one to look for reasons why the hypothesis is a good one; a second to look for reasons why it isn’t; and a third to judge which of the other two is correct.

Another area where AI shows promise is selecting patients for trials. It can analyse candidates’ health records, biopsies and body scans to identify who might benefit most from a novel drug. Better choice of participants means smaller—and thus faster and cheaper—trials.

The most intriguing use of AI to improve trials, though, is the creation of synthetic patients (sometimes called digital twins) to act as matched controls for real participants. To do this an AI goes through data from past trials and learns to predict what might happen to a participant if they follow the natural course of their condition rather than being treated. Then, when a volunteer is enrolled in a trial and given a drug, the AI creates a “patient” with the same set of characteristics, such as age, weight, existing conditions and disease stage. The drug’s efficacy in the real patient can thus be measured against the progress of this virtual alternative.

If adopted, the use of synthetic patients would reduce the size of trials’ control arms and could, potentially, eliminate them entirely in some cases. Their use might also appeal to participants, since the chance of receiving the treatment under test rather than being put into a control group without it would rise.

Work published in 2025 by Unlearn.AI, a digital-twins firm in San Francisco, suggested that this approach could have reduced the size of a control arm in an early Parkinson’s disease trial by 38%, and by 23% in a different study on Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, early-stage trials in general, which sometimes lack a control arm altogether, could now introduce these digitally to enhance confidence in signs of efficacy, and improve the way subsequent trials are designed.

Recursion, a firm in Salt Lake City, has built an AI “factory” in which millions of human cells are pictured undergoing various chemical and genetic changes. That allows AIs to learn patterns connecting genes and molecular pathways. And Owkin, an AI biotech in New York, is training its model on a vast set of high-resolution molecular data from hospital patients.

Tom Clozel, Owkin’s boss, argues that by making discoveries which humans cannot, this work is moving towards true artificial general intelligence in biology. That raises the question of whether conventional pharma companies are at risk of disruption by upstart AI firms.

Companies such as OpenAI, which led development of the transformers known as large language models, and Isomorphic Labs, a drug-discovery startup spun out of Google DeepMind, are already training systems to reason and make discoveries in the life sciences, hoping these tools will become capable biologists. For now, drug firms have the advantage of a wealth of data and the context to understand and use it, so collaboration is the order of the day. OpenAI, for example, is working with Moderna, a pioneer of RNA vaccines, to speed the development of personalised cancer vaccines. But as the new models make biology more predictable the balance of advantage in the industry may change.

Regardless of that, AI has already improved things greatly. If it can wring from late-stage trials the sorts of improvement it has brought to the earlier part of the process, the number of drugs arriving on the market should rise significantly. In the longer run, the possibilities for enhancing human health are enormous.